by Christopher Hongach

Often neglected from the discourse of climate change environmentalism are prisons and prison inmates. By exposing the embedded social injustices that have structured the prison industrial complex in the United States, the overlapping and intertwined effects of racism, capitalism, and imperialism reveal how certain bodies, particularly Black bodies, are targeted, exploited, and made disposable, at the sanction of state and neoliberal powers.

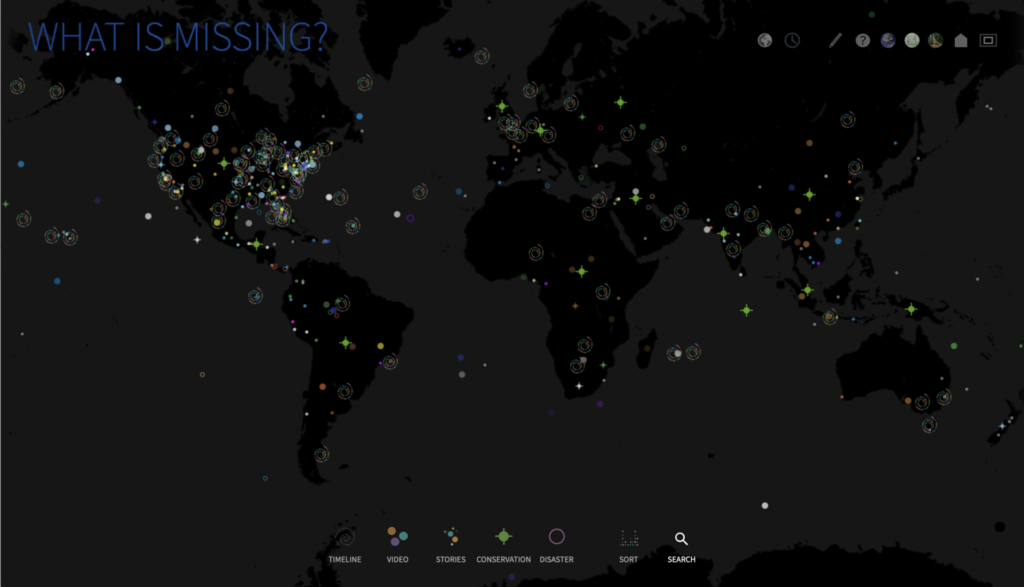

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/americas/us-prisons-building-catalogs-of-inmates-voices-report/1380458

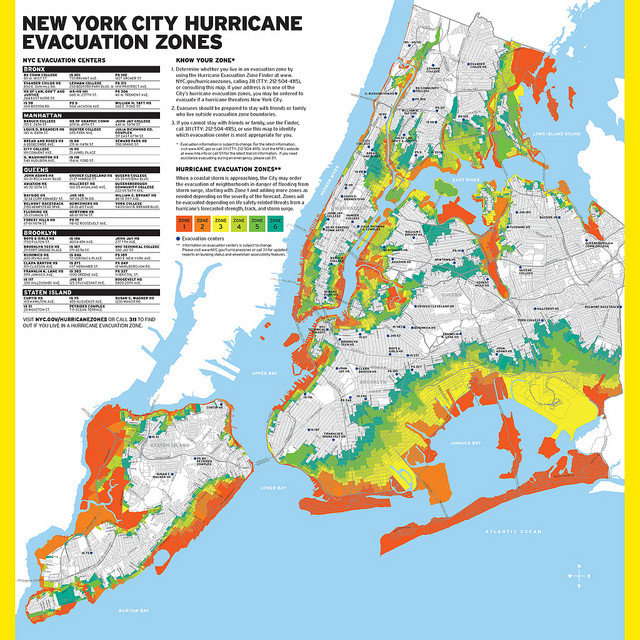

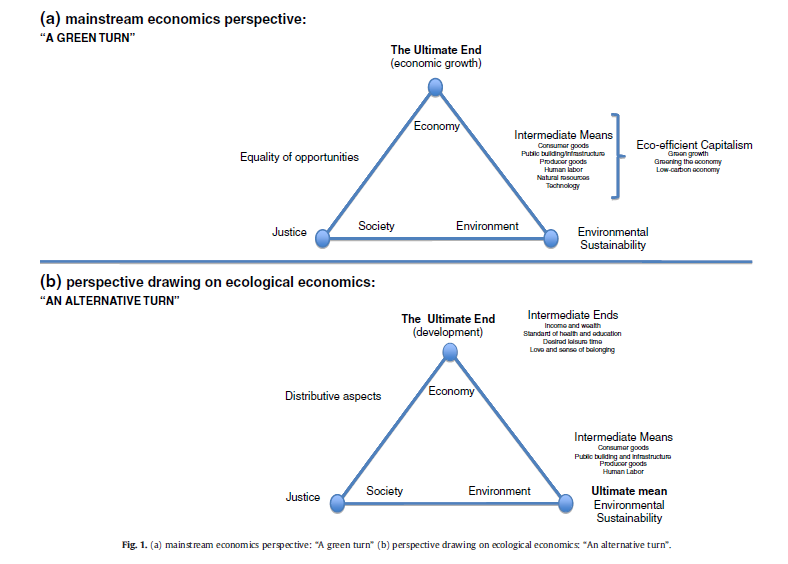

One of the most challenging components of climate change discourse is the establishment of inclusivity. With a society structured on differences and divisions, it seems collectivizing politically for climate change initiatives is nearly impossible. Even emphasizing democratic principles has its short-comings in the establishment of inclusivity, specifically as they operate within state power, both ideologically and institutionally. In order to uphold the essential democratic principles, a policing and a “securitizing” system must exist within state power over society. Understanding this means understanding that there is inherent “otherness” to a society. Upon conviction of certain violations, “others” become “the incarcerated,” who, then, endure the oppression enforced upon them by state power and its supported agencies.

Once convicted, persons are completely dehumanized; closed off from society and open social and political participation, prisoners are cut off the world.

Prisoners line up to vote at the D.C. Jail in Washington, DC.Jacquelyn Martin/AP. https://www.motherjones.com/crime-justice/2018/02/the-race-gap-in-u-s-prisons-is-glaring-and-poverty-is-making-it-worse/

Due to the war on drugs and the war on crime, from the 1970’s onward, America saw the rise of prisons and, with that, an increase in incarceration in the population. These changes, occurring after the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960’s, most effectively targeted Black communities. Today, while there are between 1.7 – 2.3 million people incarcerated in the U.S. (or 1/200 people), Black men make up the largest percentage of the incarcerated population in the U.S. (about 1/100 Black people are incarcerated; with 1/3 Black men being incarcerated).

The increase of prisons and prisoners are part of the prison industrial complex, which seeks to address social issues with incarceration, rather than with sophisticated investments in true rehabilitative resources or social equity.

Other features of the prison industrial complex reveal neoliberal agendas that further imprison the incarcerated and violate their human rights, such as the cost-cutting effects on prisoner’s essential needs or through the violating practices of prison labor.

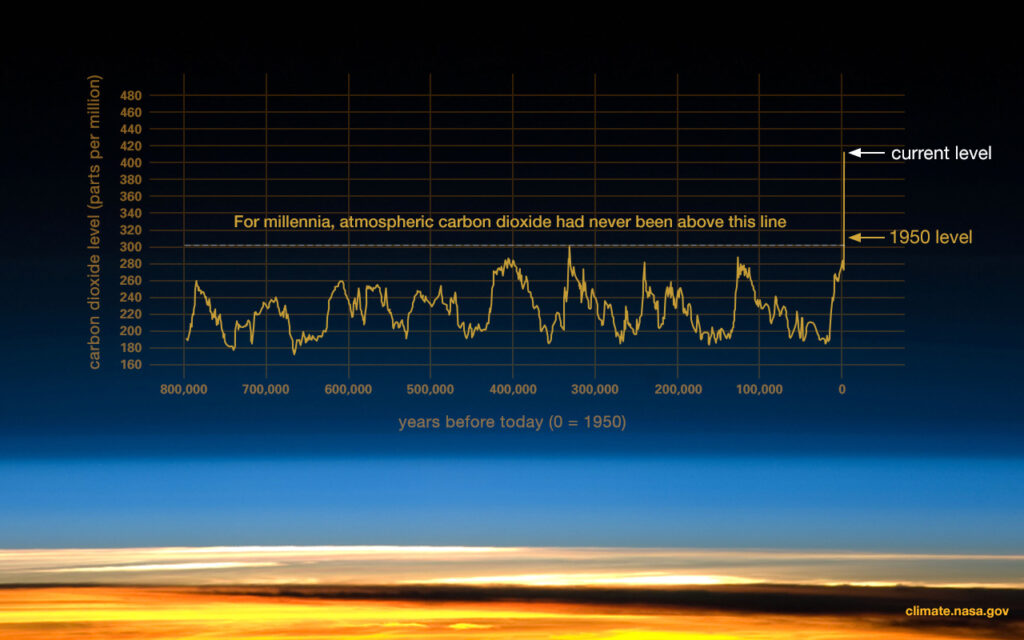

In circumstances of climate change, prisons have especially experienced exploitation and disposability by state and neoliberal forces.

Prisons like SCI Fayette in Pennsylvania, built near a coal dumping grounds, seemingly geographically out of reach of social centers, endure the toxicity of coal ash contamination of water and air, leaving prisoners with serious complications to their health.

Other prison issues pertaining to climate change, like in California, where global warming has significantly contributed to the damages caused by forest fires, exposes the issues of prison labor. Inmate firefighters, who make up 30-40% of California’s fire fighters, receive barely any training and close to nothing in compensation to be on the frontlines of service.

An inmate firefighter pauses during a firing operation as the Carr fire continues to burn in Redding, California on July 27, 2018. Josh Edelson | AFP | Getty Images. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/08/14/california-is-paying-inmates-1-an-hour-to-fight-wildfires.html

Understanding how the incarcerated are exploited, abused, and discarded is only the first step to rectifying the faults in our “liberal democracy.”

The racial aspect of prisons, as it relates specifically to climate change environmentalism, is a particular point of focus which highlights the layers of racism, capitalism, and the unconstitutional practices of imperialism that are embedded in the greater issues of climate injustice for the prison population of the United States.

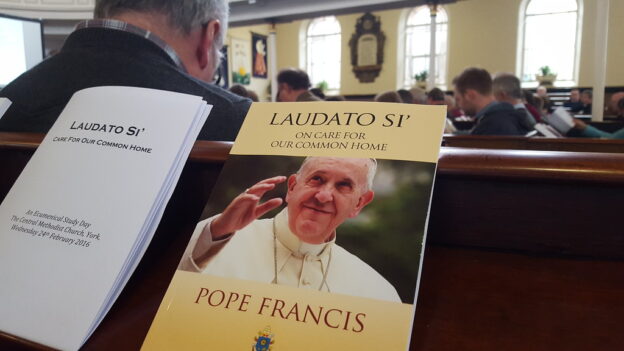

Arguing for the remembrance of “the disposable” mass of the incarcerated, who, in various locations across the U.S., are left out of the discourses on climate change injustice, helps reveal the hypocrisies of our American liberal democracy, by exposing the deeply embedded social injustices that have structured the prison industrial system and by exposing the cruel and unusual punishments put upon them from the unconstitutional practices by biopolitical power forces.

We must not only remember the incarcerated in the discussions of climate justice, but we must critically address the embedded social injustices that structure the prison industrial complex and allow climate injustice to persist.

We must put aside structural racism and clauses of biopolitical eugenics written in our legal codes; rectify the symbolics of our certain harmful social understandings; and end the infrastructures of oppression, by legitimate democratization of social and climate participation.

By outlining community efforts inside, between, and outside prisons in the U.S., such as by the involvement of advocacy groups and media enhancement, we make achievable the possibilities of social and climate solidarity.

Main Sources

Barroca v. Bureau of Prisons. District of Colombia, Case 1:18-cv-02740-JEB, Document 12. 23 April 2019.

http://abolitionistlawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/amended-complaint-Barroca.pdf

Bernd, Candice; Zoe Loftus-Farren; and Maureen Nandini Mitra. “America’s Toxic Prisons: The Environmental Injustices of Mass Incarceration,” Earth Island Journal and Truthout. 2018.

https://earthisland.org/journal/americas-toxic-prisons/

Borunda, Alejandra. “Climate change is contributing to California’s fires,” National Geographic. 25 October 2019.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2019/10/climate-change-california-power-outage/

The Campaign to Fight Toxic Prisons. “No Escape: Exposure to Toxic Coal Waste at State Correctional Institution Fayette.” Abolitionist Law Center and Human Rights Coalition.

https://abolitionistlawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/no-escape-bw-1-4mb.pdf

Carson, E. Ann. “Prisoners in 2018.” Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, NCJ 253516. April 2020.

https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p18.pdf

Democracy Now. “$1 an Hour to Fight Largest Fire in CA History: Are Prison Firefighting Programs Slave Labor?” Democracy Now. 9 August 2018.

https://www.democracynow.org/2018/8/9/1_an_hour_to_fight_largest

Duncan, Sophie. “Prison Labor in a Warming World: When floods and fires strike, who has to clean up the mess?” The Free Radicals. 14 August 2018.

Equal Justice Initiative, “News: Investigation Reveals Environmental Dangers in America’s Toxic Prisons.” 16 June 2017.

https://eji.org/news/investigation-reveals-environmental-dangers-in-toxic-prisons/

Evans, Brad and Henry A. Giroux. Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of the Spectacle. City Lights Books. 2015.

Flood the System. “Infographic: Prisons and Climate Change,” Flood the System.

Gotsch, Kara and Vinay Basti. “Capitalizing on Mass Incarceration: U.S. Growth in Private Prisons,” The Sentencing Project. 2 August 2018.

Greenfield, Nicole. “The Connection Between Mass Incarceration and Environmental Justice,” NRDC. 19 January 2018.

https://www.nrdc.org/onearth/connection-between-mass-incarceration-and-environmental-justice

LeRoy, Carri J; Kelli Bush, Joslyn Trive, and Briana Gallagher. “Suitability in Prisons ProjectL An Overview (2004–12),” Washington State Department of Corrections & The Evergreen State College. 2013.

http://sustainabilityinprisons.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Overview-cover-text-reduced-size.pdf

Lorie, Julia. “30 Percent of California’s Forest Firefighters Are Prisoners,” Mother Jones. 14 August 2015.

Rakia, Raven. “A sinking jail: The environmental disaster that is Rikers Island,” Grist. 15 March 2016.

Sabalow, Ryan. “These California inmates risked death to fight wildfires. After prison, they’re left behind,” The Sacramento Bee. 23 July 2020.

https://www.sacbee.com/news/california/fires/article244286777.html

The Sentencing Project, “Issues: Felony Disenfranchisement,”

https://www.sentencingproject.org/issues/felony-disenfranchisement/

Taiwo, Olufemi O. “Climate Apartheid Is the Coming Police Violence Crisis,” Dissent Magazine. 12 August 2020.

Tsolkas, Panagioti. “Prisoners File Unprecedented Environmental Lawsuit against Proposed Federal Prison in Kentucky,” Nation Inside. 7 December 2018.

Wang, Jackie. Carceral Capitalism. Semiotext(e) Intervention Series, 21. 2018.

Yusoff, Kathryn. “Geology, Race, and Matter,” A Billion Black Anthropocenes of None. University of Minnesota Press. 2018.

Further Questions:

- How does the prison industrial complex affect other communities–such as Latin-x communities, LGBTQ+ communities, and women? What can we say about intersectionality and the prison industrial complex?

- If prisons are abolished, what about social safety? Is investing in the community and social welfare programs really a more dignified, effective solution?

- What does a “Marshall Plan”-like economic aid look like for social inequalities, or for climate change initiatives? How would this money get handled?

- Even if prisons are reformed, to the extent that living and working conditions are improved, and prisoners are not recruited into the front lines of climate change clean up, what is there to say about neoliberal privatized police and prisons, as climate change continues to increasingly effect the way we live?

- Is climate change the next big shift in policing and incarceration? How does this tie directly into capitalism and, even, racism?

- Is an universal, all-inclusive climate change discourse possible?