Abstract

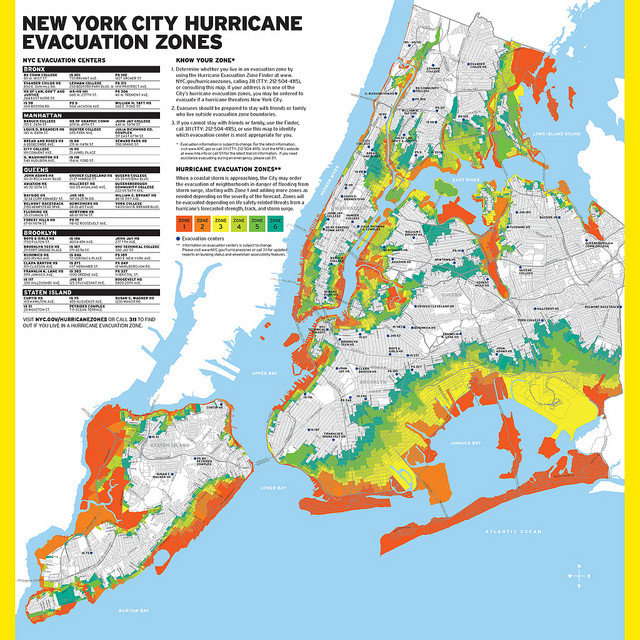

Coastal resiliency, or the defense against extreme weather events, is becoming significantly more critical to the livelihood of coastal communities as the frequency and intensity of storms increases and is exacerbated by rising sea levels due to climate change. In 2012 Superstorm Sandy cost $42 billion across New York State in structural damage and displaced many residents from their homes for prolonged periods of time as storm surges surpassed record highs for the region. New York’s coastal communities need to be better prepared for future climate related scenarios and resiliency planning needs to include protection of public health and safety, reduced risk of structural and non-structural damage, and improved recovery strategies. Coastal wetlands provide a critical line of defense against more intense and frequent weather events due to their ability to mitigate storm damages by providing natural resistance from flooding through rainwater absorption, protecting shorelines from erosion by buffering wave action and sediment capture, as well as their capability to naturally accrete, or build up vertically, to contend with sea level rise trends. In this paper I will explore how to best bring the scientific research and evidence of the anthropogenic impacts to tidal wetlands to a practical level of understanding on the community level. By building connections between the community and the natural coastal landscape, a sense of care for the environment and a relationship to the value it has for coastal resiliency is more likely to develop among residents, which may significantly improve the success and sustainability of coastal wetland restoration and management initiatives.

Credit…Mandel Ngan/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Significance of coastal wetland ecosystems

Coastal wetlands are highly productive areas that provide important ecosystem services. These environments contain a diversity of native vegetation and support abundant aquatic, avian, and terrestrial wildlife. Healthy functioning wetlands also improve water quality by filtering stormwater runoff and metabolizing excess nutrients which is critical for clarifying the water and creating more suitable conditions for natural resource and commodity production and supporting commercial and recreational estuary-related business.

These ecosystems are also vital in in the context of climate change and sea level rise. Tidal wetlands have important carbon sequestration abilities and may be significant in relation to the urgency to reduce global carbon footprints contributing to planetary warming. Vigorous wetland conditions also provide protection to public health and infrastructure by providing natural resistance to storms and flooding which is increasingly becoming more important with rising seas and more frequent extreme weather events. Protection and restoration of the natural estuarine environment and its ability to mitigate storm damages should be of the highest priority for New York’s coastal communities.

Interacting stresses on tidal wetlands

Historical anthropogenic impacts to New York’s coastal wetlands over the last century such as grid-ditching existing marshes for mosquito control, filling of wetlands for development, construction of infrastructure segmenting habitat, and displacing native species with human introduced non-natives has caused ecosystem degradation and loss of wetland acreage. Further degradation of tidal wetland habitat has occurred due to urbanization and indeed much of New York’s population is concentrated around these coastal environments. In fact, coastal wetland systems arguably serve more human uses than any other ecosystem and are the sites of the world’s most intense commercial activity and population growth with approximately 75% of the worldwide human population living in coastal regions.

Anthropogenic eutrophication, or excess nutrient inputs to coastal system from human activities, has become a serious problem; nitrogen being the primary nutrient of concern for waters in the New York region. Nitrogen inputs to New York’s coastal estuarine systems from human land uses generally originate from fertilizers, stormwater runoff and combined sewer overflows (CSOs), and wastewater systems. Excess anthropogenic nitrogen inputs promote a series of positive feedbacks by altering ecosystem processes leaving coastal wetlands more susceptible to the erosive forces of storms, sea level rise, and gravitational slumping. This cascade of changes can eventually result in deficient ecosystem functioning, threaten the long-term stability of marsh systems, and cause wetland acreage loss. Climate change can further compound these issues since areas in the Northeast U.S., including New York, are expected to experience increases in precipitation as well as warmer conditions during the winter months, resulting in more precipitation as rain and less as snow, which can increase the frequency of runoff events. More stormwater runoff and CSOs translates to higher levels of nitrogen reaching estuarine habitats and increased levels of degradation to wetlands.

Mark Bertness. http://www.bertnesslab.com

Connecting communities to wetlands through management and restoration

Nutrient management policy implementation paired with wetland restoration projects can potentially repair damages to tidal marsh habitats and thus preserve their healthy ecological functioning and the ecosystem services that they provide to coastal communities including coastal resilience. However, many residents in New York’s coastal communities who live in close proximity to these habitats and are largely contributing anthropogenic eutrophication through their everyday activities, may not see the intricate connections, which I have endeavored to lay out in my paper, that wetland ecosystems indeed have to their everyday lives. I argue that improvements in communication and engagement with local communities as well as fostering an environmental ethic can significantly improve wetland restoration and management efforts.

Fresh Kills in Staten Island, NY was wetland habitat that was valued so low that is was opened as a landfill in 1948 to be a receptacle for New York City’s garbage and became one of the world’s largest dumps. Fresh Kills Landfill was closed by Governor George Pataki and Mayor Rudy Giuliani in 2001 and the site is currently undergoing restoration. This work includes restoring 360 acres of wetlands and reclaiming 1,000 acres of higher elevated areas previously altered by landfill operations as grasslands (also an important carbon sink) to transform the area into “an extraordinary 2,200 acre urban park that will be a model for sustainable waterfront land reclamation, a source of pride for Staten Island and New York City, and a gift of open space for generations to come” (https://freshkillspark.org/). This is a really beautiful and, for me, emotional “ugly duckling story” and may serve as an inspiration for other potential ecological restoration and reclamation projects which will be so important for coastal resiliency, carbon sequestration, climate change, and our future.

Chester Higgins, Jr. – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

(Photo: Alex MacLean)

Public education and outreach campaigns are valuable for cultivating community engagement with wetland protection, management, and restoration efforts but importantly need to focus on creating a dialogue and participation between scientists, government, and the public. Communities especially need to be persuaded that a series of incremental actions and behavior changes that they are indeed themselves capable of carrying out has the potential to accomplish significant changes to our coastal wetland ecosystems. The incorporation of in-field education and volunteer activities as well as recreational opportunities is also essential to create a sense of place and can very often, in turn, bring a sense of care to the environment. In these ways new frameworks for environmental stewardship could be better put into action both on the ground within local communities and at broader national and international socio-ecological levels.