A class project, by Lala St. Fleur

Summary

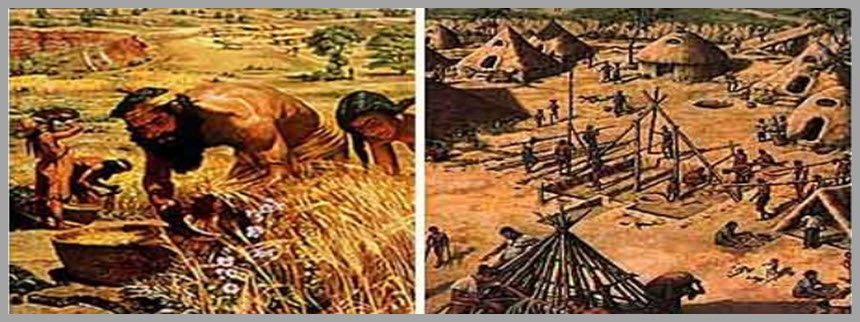

In arguments over the technical terminology of referring to climate change, and its associated social and environmental crises, as anthropogenic (the fault of all mankind) or capitalogenic (the fault of modern industrial-capitalist institutions), my reflexive 21st century instinct is to blame capitalism for all of the problems of modern-day society, including environmental degradation. However, it also cannot be denied that there have been grave mistakes of the distant past that peoples of the immediate present and potential future are still paying for. I stand with paleoclimatologist William F. Ruddiman’s understanding of the Anthropocene as having started over 10,000 years ago, during the Agricultural Revolution, when mankind moved from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to sedentary agrarianism (Ruddiman, 2003: 261). I disagree with the notion that the Anthropocene having started during the Industrial Revolution, as Paul J. Crutzen more popularly defined it.

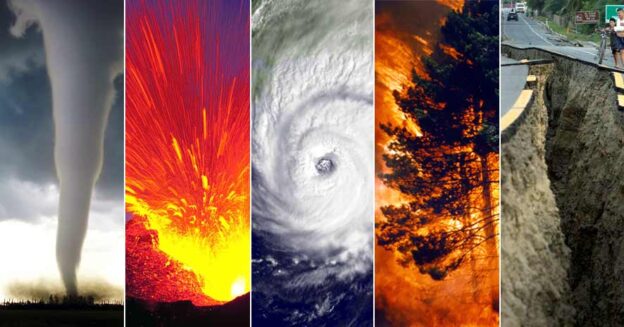

Around the world, there are longstanding religious beliefs that the natural forces — or rather, nature spirits — of the earth itself are acting out in warning, protest or punishment against the decay of societies that have lost faith and not kept to the old ways of their forebearers. My research paper analyzes etiological and eschatological stories from ancient Greek and Abrahamic religions, that see certain elemental forces (Fire and Earth) and geological events (natural disasters) as manifestations of divine punishment against the wrongdoings of mankind. These stories are directly tied to the Agricultural Revolution.

Earth: The Agricultural Revolution

In the Book of Genesis’ story of Adam and Eve, the first man and woman were expelled from the Garden of Eden after eating the Forbidden Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. As punishment, God exiled Adam and Eve from Paradise, and so, stuck on earth, they had to work the land as farmers, toiling by the sweat of their brow for everything they ate. But the earth was now cursed, and by extension, so were the fruits of all their labor. This story can be seen as reflecting mankind’s transition from hunter-gatherers to agrarian societies.

Cursed is the ground for your sake;

Genesis 3:17

In toil you shall eat of it

All the days of your life.

The story of Adam and Eve’s sons, Cain and Abel, are also interpreted in my paper as allegorical, with Cain representing agrarianism and Abel representing pastoralism. In both Genesis stories, agriculture is directly tied to the sin of hubris. Adam and Eve sought forbidden knowledge. Cain thought his sacrifice of grain was better than Abel’s blood sacrifice of his first flock. In both stories, humans act against the will of God, and both mankind and the land itself suffer for it.

My paper connects these biblical stories with archaeological scholarship on Neolithic societies in the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia. Scholars either support or reject the notion that the Agricultural Revolution directly led to not only the formation of sedentary societies and the first cities, but also socio-economic inequality, and anthropogenic environmental degradation (Marcus and Sabloff 2008; Watkins 2006).

Fire: The Industrial Revolution

Rather than examining the Anthropocene through the modern Industrial Revolution of the 1800s, as Crutzen does, instead, my paper looks to ancient stories that describe the Fall of Man, related to technology, industry, and modernity.

In the apocryphal Book of Enoch, heavenly angels described as the Watchers descend to earth to breed giants with humans. They also taught humanity various corruptible knowledge, including, but not limited to warfare. Chief amongst them is Azazel, the Scapegoat.

Heal the earth which the angels have corrupted, and proclaim the healing of the earth, that they may heal the plague, and that all the children of men may not perish through all the secret things that the Watchers have disclosed and have taught their sons. And the whole earth has been corrupted through the works that were taught by Azâzêl: to him ascribe all sin.

Book of Enoch, 10:7-9

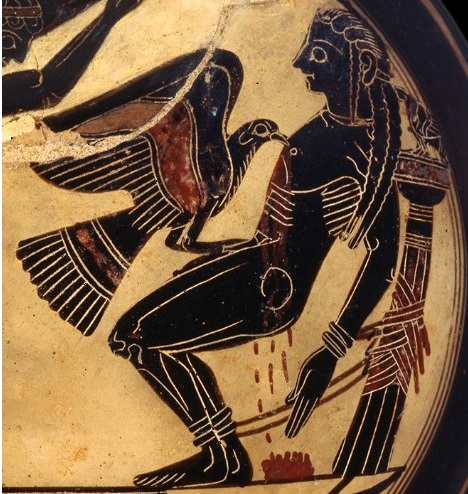

This apocryphal Abrahamic story serves as the segue into my segment on Greek mythology, which features another major etiological figure connected to human progress and punishment, the Titan Prometheus.

My paper uses myths from the poets Hesiod and Aeschylus to highlight the ways that the mastery of fire, technological advancement and human innovation were considered the very foundations of civilized society, as early as the 8th-5th centuries B.C.

Hearken to the miseries that beset mankind how that they were witless before and I [Prometheus] made them to have sense and be endowed with reason.… Knowledge had they neither of houses built of bricks and turned to face the sun, nor yet of work in wood; but dwelt beneath the ground like swarming ants, in sunless caves.

Hesiod, Works and Days, 42-50.

Prometheus bestowed fire to cavemen, teaching them how to master it, and thereby inspiring the development of everything from architecture to art and science. However, Zeus, king of the gods, was angered at humanity gaining access to heavenly fire. As punishment, Prometheus was imprisoned, to be tortured for all eternity, and mankind was given the all-gifted woman, Pandora, of “Pandora’s Box” infamy. Upon opening her jar or box, Pandora unleashed all evils upon the world, including disease, poverty, and warfare.

Up to the present day, Prometheus has been perceived as either a savior god of industrial creativity, or as the corrupting demiurge of industrial destruction (Beller 1984).

By synthesizing the lessons to be gleaned from the stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Azazel, and Prometheus, and analyzing their parallels with archaeological research, my class project attempts to stimulate an alternate way of thinking about certain things we take for granted: What does it mean for humanity to have evolved, developed, and progressed–even at the expense of the natural environment, and our own societal well-being?

World religions have long held people’s moral decay accountable for environmental decay. Regardless of whether or not climate change is the result of man’s faults in the anthropogenic past or capitalogenic present, the record still shows that it is essentially, fundamentally and ultimately humanity’s fault. The only arguments should be grounded in what we are going to do about it now, to save both the planet, and ourselves.

Resources

- Aeschylus. Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. 1. Prometheus Bound. Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1926.

- Anonymous. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1914.

- Beller, Manfred. “The Fire of Prometheus and the Theme of Progress in Goethe, Nietzsche, Kafka, and Canetti.” Colloquia Germanica 17, no. 1/2 (1984): 1-13.

- Charles, Robert Henry. Book of Enoch: Spck Classic. SPCK, 2013.

- Crutzen, Paul J. “The ‘Anthropocene’.” In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene, pp. 13-18. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006.

- Demos, Thomas J. “Against the Anthropocene.” Visual Culture and Environment Today (2017): 132.

- Marcus, Joyce, and Jeremy A. Sabloff, eds. The Ancient City: New Perspectives on Urbanism in the Old and New World. School for Advanced Research, 2008.

- Ruddiman, William F. “The Anthropogenic Greenhouse Era Began Thousands of Years Ago.” Climatic Change 61, no. 3 (2003): 261-293.

- Steffen, Will, Paul J. Crutzen, and John R. McNeill. “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature.” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 36, no. 8 (2007): 614-621.

- Stoekl, Allan. “Marxism, Materialism, and the Critique of Energy.” In Materialism and the Critique of Energy,” edited by Brent Ryan Bellamy and Jeff Diamanti, 1-29. MCM, 2018.

- Watkins, Trevor. “Neolithisation in Southwest Asia—The Path to Modernity.” Documenta Praehistorica 33 (2006): 71-88.

Discussion Questions

- Why is it that more often than not, popular culture props Prometheus the Titan up, while castigating Azazel the Scapegoat, Eve (moreso than Adam), and Cain?

- What is “progress”? Has humanity evolved, or devolved?

- Is hunter-gathering or agriculture better for the environment? To what extent could modern man ever return to either model?

- Is technology/industry worth moral & environmental decay?

- What are we willing to sacrifice to make things right?