A reading response, by Lala St. Fleur

The social consequences of putting deep ecology into practice on a worldwide basis (what its practitioners are aiming for) are very grave indeed.

Ramachandra Guha, Environmental Ethics, 1989.

Environmentalist Subhankar Banerjee’s 2016 paper, “Long Environmentalism: After the Listening Session,” demonstrates how indigenous resistance movements inadvertently highlight the pitfalls of certain conservationist issues that prioritize nature over human beings. Banerjee coined the term “long environmentalism” in reference to ongoing environmental engagements that create their own histories and cultures of environmentalism (2016: 62). According to Banerjee, long environmentalism can foster coalitional relationships between indigenous people and government institutions, by doing four things: (2016: 62-63)

- illuminating past injustices

- highlighting the significance of resistance movements to avert potential social-environmental violence (fast and/or slow)

- showing how communities respond to slow violence, and

- pointing towards social-ecological renewal after devastation

This is especially important in the face of biocentrism, or deep ecology, where nature is given “ethical status at least equal to that of humans,” to the point that the preservation of nonhuman biotic life and biospheres becomes is served to the detriment of preserving indigenous ways of life, (2016: 63).

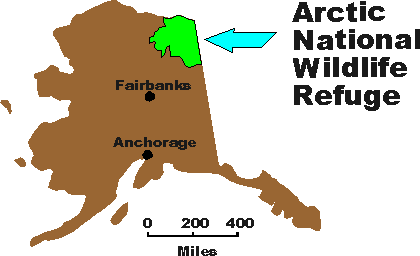

Banerjee’s paper uses the plight of the Gwich’in and Iñupiat Alaskan natives as case studies for examining ways that environmental conservationist concerns need to be reconciled with the protection of human rights. For decades, Alaska’s indigenous tribes have found themselves in land disputes against the American government over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, cordoned off by the Public Land Order of 1960. This Alaskan coastal territory held precious oil and gas reserves for industrialists; pristine wilderness land conservationists lobbied to protect; and “nutritional, cultural, and spiritual sustenance” for the Gwich’in and Iñupiat (2016: 65).

Arctic_National_Wildlife_Refuge, Wikimedia Commons

Arctic_National_Wildlife_Refuge, Wikimedia Commons

With the indigenous cultural traditions enacted in their own homeland criminalized as everything from poaching, arson, and outright theft by the conservationists, the Alaskan indigenous groups were summarily stripped of their rights to access their own ancestral land, all for the sake of “preserving unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values,” of white tourists and conservationists, not the original inhabitants, (2016:67).

Hard-fought coalitions like the 1980 Alaska National Interest Land Conservation Act (ANILCA) and the 1988 Gwich’in Steering Committee have worked to bring together tribes and environmentalists to both protect precious wilderness from drilling and deforestation, as well as protect indigenous rights to subsistence hunting–though the former is often prioritized over the latter.

Banerjee’s paper reminded me of other instances where eminent domain was enforced in the name of environmentalism, to the detriment of the original inhabitants. As a resident of New York City, my mind was immediately taken back to the creation of Central Park, the emerald jewel in the heart of Manhattan’s concrete jungle.

Central Park was the magnum opus of New York City’s 19th century Environmental Movement, which was a direct response to the the destruction of the natural landscape and shrinking of the “green” environment of the city, as the rapid industrialization, urbanization, and population boom of the mid-1800’s took over what was once lush wilderness. Municipal sanitation was still in its infancy, and in no position to tackle the overwhelming pollution littering the streets.

The city is dirtier and noisier, and more uncomfortable, and drearier to live in than it ever was before. I have bad my fill of town life, and begin to wish to pass a little time in the county.

William Cullen Bryant, romantic poet (Letters, September 1836: 87).

Inspired by the writings of naturalists and reformers including Henry Thoreau, Ralph Emerson, and Horace Greely, landscape architects Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were hired by NYC in 1858 to beautify the city, and create a public park in the spirit of environmental preservation. Thus, Central Park was born, the most visited urban park in the USA, and most filmed location in the world.

However, what is not so famously known is that in order to create Central Park, an entire community of over 1600 free African-Americans who lived on that land from 1825 – 1857 were forced off of their property through eminent domain; their communities scattered throughout parts of NYC and New Jersey; their homes leveled so that Central Park could be built.

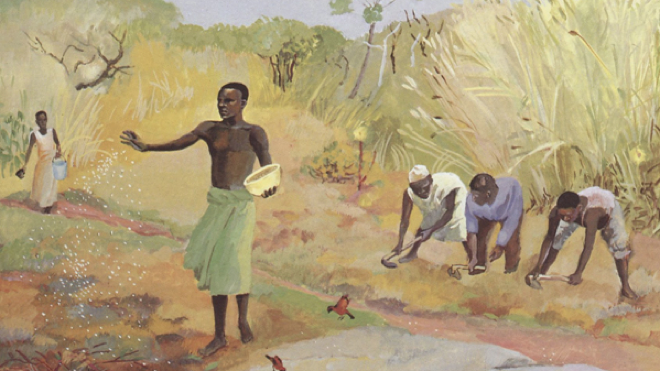

A temporary outdoor exhibit, called Discover Seneca Village.

Remnants of Seneca Village were uncovered in a 2011 excavation by archaeologists from Columbia University and CUNY schools. Amidst the foundations of Seneca Village’s buildings were several thousand 19th-century artifacts, including household items and other abandoned or discarded personal effects.

With Seneca Village and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in mind, one really must consider both the benefits and pitfalls of unchecked industrialization and development, as well as overzealous and inconsiderate environmentalist movements. There have been amazing strides taken to preserve natural landscapes and endangered biospheres. But there have also been heinous crimes committed against the rights and lives of human beings, who are disenfranchized by biocentric conservationists who care more about land than the people who live in it.