An annotated bibliography, by Lala St. Fleur.

Core Text

Demos, Thomas J. “Against the Anthropocene.” Visual Culture and Environment Today (2017): 132.

Summary

Demos’ 2017 book is firmly against using the term “Anthropocene” in reference to the ongoing concerns around climate change. In Demos’ view, it only foists the blame of the military-state-corporate interests off onto universal accountability held by all of humanity, rather than to those truly at fault or most responsible for the world’s mounting eco-catastrophes (Demos, 2017: 19). He also challenges the emphasis put on geoengineering projects as solutions to environmental problems. Because the authority to conduct such experiments inevitably favors an imbalance of power between individuals, governments and corporations, Demos is skeptical of anthropocenologists (i.e.: military-state-corporate agents) having the final say as to what measures should be taken to see positive change and real environmental improvement.

Because the “Anthropocene” holds all humans accountable for global climate change, Demos argues that it disavows the unequal distribution of resources, aid, and responsibility between parties who either suffer or benefit the most from its causes and effects. It is the “underlying heteropatriarchal and white supremacist structures” whose fossil fuel industries are the worst perpetrators of environmental abuse, (Demos, 2017: 53). Meanwhile, disenfranchized and poor minorities are most severely affected by the slow violence of government policy, corporate interests, and climate impact. But the consolidated efforts of grassroots activism inside those very communities are also in a position to resist such pressures and hold corporations accountable for their harmful operations. In place of “Anthropocene,” Demos proposes the adoption of the term “Capitalocene” instead. Demos sees this as a “more accurate and politically enabling geological descriptor” for more precisely putting the blame on corporate globalization and industrialization as the main culprits of unchecked climate change (Demos, 2017: 54).

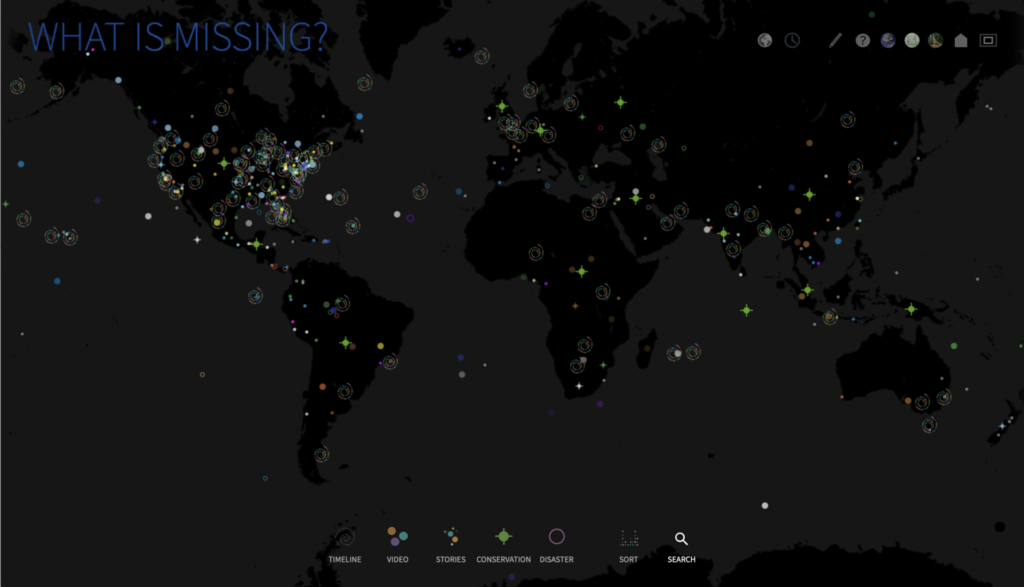

Demos’s methodology involves looking at the utilization of photo imagery circulated by the media and academia, as visualizations that either help shed light on climate crises that corporations would otherwise see silenced (local activism against fracking or development in communities; the victims of marine pollution and oil spills); or help divert attention away from environmental concerns by glorifying mankind’s dominion over nature (incredible mines seen from space; the downplay of the effect of said oil spills; etc.).

Teaching Resources

- Crutzen, Paul J. “The ‘Anthropocene’.” In Earth system science in the anthropocene, pp. 13-18. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006. Atmospheric chemist Paul J. Crutzen is the scholar who popularized the use of the term “Anthropocene,” in 2000. In this 2006 article, he doubles down on his notions that the current Anthropocene age (starting with the Industrial Revolution) is distinct from the Holocene’s epoch of pre-industrial human activity. Despite Earth’s cycles and systems of global change, Crutzen argues that anthropogenic activity has gone far beyond the bounds of natural atmospheric, chemical, and geological fluctuations.

- Stengers, Isabelle. In catastrophic times: Resisting the coming barbarism. Open Humanities Press, 2015. In this rapidly changing epoch, Stengers’ book acknowledges the sense of impotency that the climate crisis can often put in the mindset of people today, who can be informed and educated about the causes of and effects of climate change (and capitalism) yet still participate in overbearing systems that perpetuate it. Stengers challenges the notions of progress and barbarism in the context of modern capitalist structures.

- Stoekl, Allan. “Marxism, Materialism, and the Critique of Energy.” In Materialism and the Critique of Energy,” edited by Brent Ryan Bellamy and Jeff Diamanti, 1-29. MCM, 2018. Though Stoekl’s article focuses on Marxist concerns of capitalist fetishism that turns both people and nature alike into commodities, he ultimately argues that “merely changing the name of the Anthropocene (to Capitolocene or whatever) would not solve the underlying social and material contradictions” of today’s climate crises (Stoekl, 2018: 55). Market-based approaches to environmental issues only serve to abstract, invert, obscure, and detract from the root problems inherent within fossil duel industries and corporate interests. Geoengineering solutions, therefore will only be protracted over millennia, “effectively implicating dozens of future generations” in an ongoing climate crisis that might never be resolved (Stoekl, 2018: 59).

Discussion Questions

- Beyond Crutzen’s interpretation, there are various other understandings of when the Anthropocene began, and what its catalysts were. Is the Anthropocene indeed the product of the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s, or is it instead a far older culture we inherited from the Agricultural Revolution and the rise of the first major civilizations, over 10,000 years ago?

- Stengers’ book focuses a light on the issue of capitalism not being all that is was cracked up to be. In the face of the various problems of modernity (climate change being only one crisis of many), what is progress, and what is barbarism? Is it progressive or barbaric to keep pushing forward with technological advancement, even at the cost of environmental decay? Or, is it progress or barbarous to actively try to dismantle institutional systems that have proved ineffective, and even dangerous to humanity and Gaia’s (the very world’s) well-being?

- What does a world without capitalism look like, and is it at all possible as long as people continue to be reliant on carbon-based technology? To what ends would any geoengineering models benefit the environment, so long as the earth’s natural resources are commodified and exploited for fuel?