A Summary of Conference Paper by Carol Joo Lee

Summary of Topic and Argument

Losses abound in the age of Climate Crisis. Faced with science that irreversible chain of events beyond human control is imminent if status quo remains, humans race to mediate and minimize the permanent disappearance of species and habitable places. These ecological and environmental disappearances, losses of our companion species and homes, are an impetus for recognizing mourning as an ethical and political response in the presence of a profound loss. In the paper, I examine the object and function of memorializing grief in relation to the ruptures in our ecosystem and biosphere through examples of contemporary “funerary art”: “Ontological turn” and new materialism offer ways in which artists are reimagining the body as a container of violent history and pollutants; and interpretations of disaster represent displacement of time and the local. In assessing artworks that respond to the urgency of these climate ruptures, I ask whether art as activism can overcome aestheticized objectification to be useful in a world defined by an existential crisis.

Summary of Research and Claims

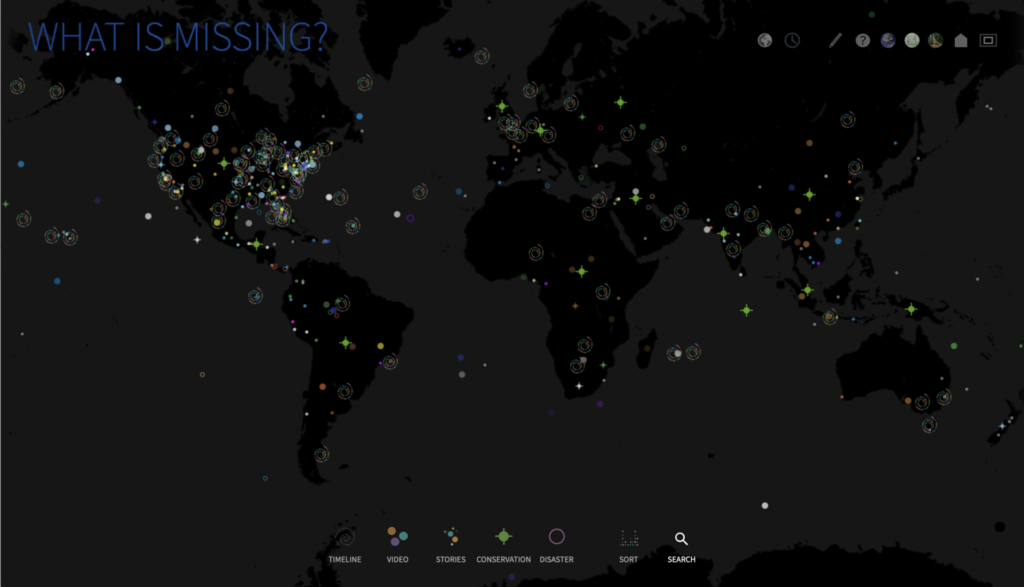

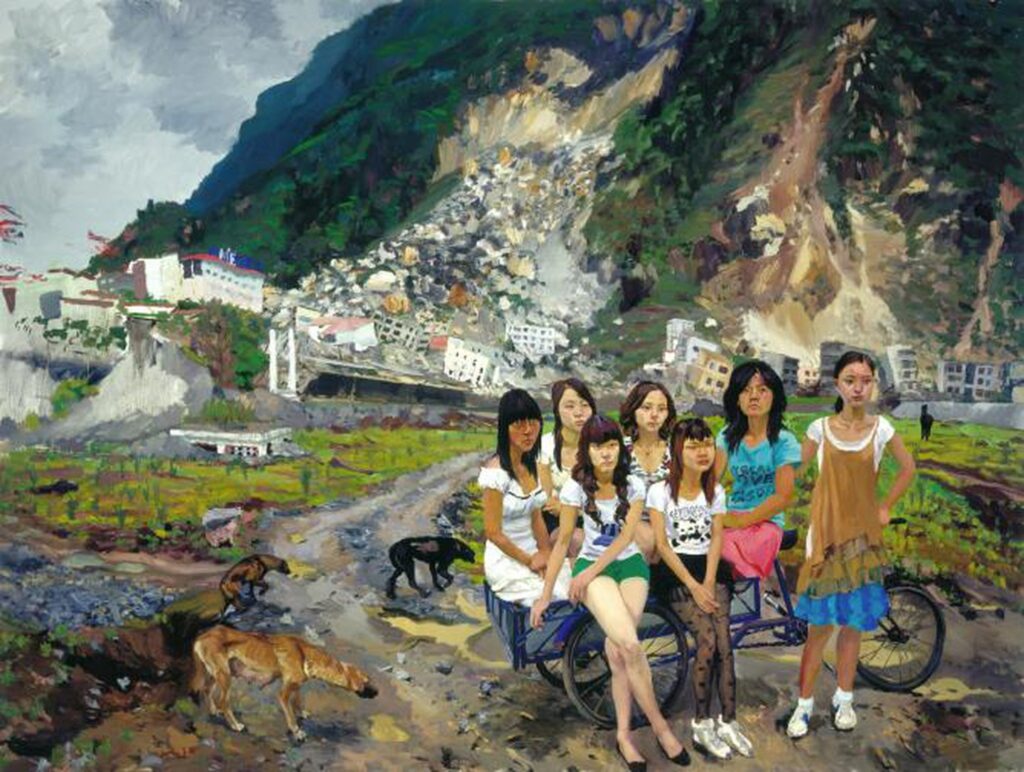

Through examples of contemporary artworks that address climatic and environmental disharmonies head on, I demonstrate mourning as an ethical and political response to ecological loss and memorializing as visualization of mourning encompassing multifaceted functions and potentials – a space for collective healing (the Vietnam Veterans Memorial); a site of recalling and confronting uneasy history (the Holocaust Memorial, “Candy Spill,” “Malinche” & “Cortés”); a point of departure for rethinking the human body in relation to nonhuman, derealized species (“States of Inflammation,” “Mushroom Burial Suit”); a template for transposing one’s own memory (“Abschlag”); and a localized cautionary tale (“Into Taihu” & “Out of Beichuan”).

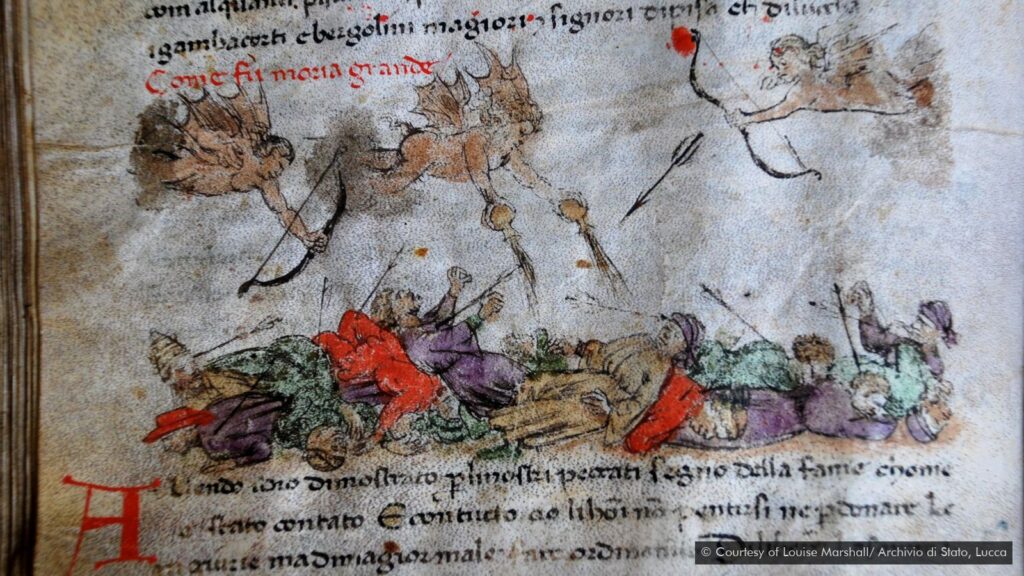

Not satisfied with widely used terms for describing our current climatic condition, I leaned into Climate Rupture to describe a breach of a harmonious relationship with the ecosystem and biosphere; ecological and environmental degradation and disappearance with implications of another mass extinction; and a culmination of disharmonies found in habits, habitats and weather. Disaster is another impetus to mourning and memorializing with additional dimension – a discombobulated time. A nexus of suddenness with permanence is one of disaster’s principal characteristics and a temporal and environmental displacement is another, as such disaster exists in the future and the present is cannibalized by the past. Anticipation of disaster is a perpetual conditioning of existing marked by anxiety of time as we race to limit global warming below 1.5°C.

Artists Thomas Hirschhorn and Liu Xiaodong confront the complex web of effects and affects of disaster directly in their work by constructing disaster as an imminent and generic phenomenon in its anywhere-ness and at once mundane and pernicious presence in the form of polluted waterway and devastating earthquake told as a localized cautionary tale. In both Hirschhorn’s and Liu’s work, a discombobulated time is woven in as an integral part of disaster: the past shows itself in the ruins of the present and resettles in the future.

In more internalized works, novel philosophical approaches such as new materialism, speculative realism and object-oriented ontology play an important role in artists’ conscious shift away from anthropocentric orientation to incorporate nonhuman perspectives and interconnectedness of natural, social and spiritual worlds. Ane Graff and Jae Rhim Lee, through their widely divergent interpretations, situate the human body as one part of the larger natural system and as both the emitter and the host of toxins with deleterious effects on nonhuman, derealized species. In Jimmie Durham’s sculptures history, ancestors and spirits are implicated (and perhaps even felt) in the heterogeneity of materials that represent the uneasy interpenetration of natural and manmade worlds, and indigenous and Western cultures.

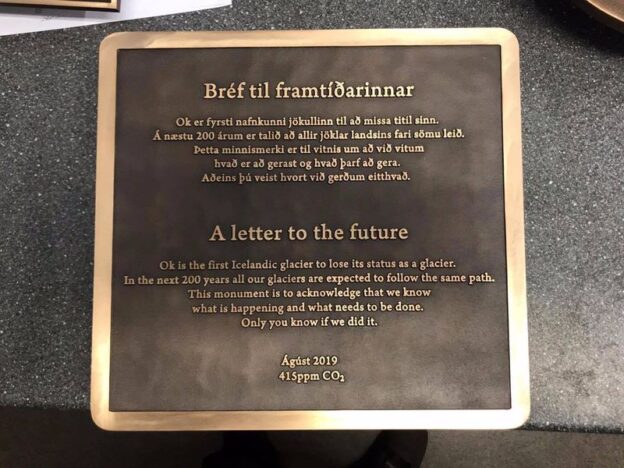

In assessing Climate Funerary Art, I framed mourning as an ethical act (Sontag) that is constitutive, rather than depreciative, with the potential to be animated for hopeful politics (Eng and Kazijian ), and the “work of mourning” as an expression of empathy “for those whom we do not know, for those whom we will not know” (Cunsolo). I argued that Climate Funerary Art in the face of large-scale losses due to climate volatility and ecological and environmental ruptures holds agency and utility, and mediates collective recognition of the loss and facilitates space for mourning and memorializing. It also enables communication between us and with the future generation.

Funerary art by definition is companion art to the body and the spirit of the dead and serves a dual function of utility and art. This allows Climate Funerary Art to escape the Groysian aestheticization conundrum and in its capacity to mourn, memorialize and accompany the dead, I argue, makes itself useful and furthermore its “being in the world” contributes to the larger discourse and visibility of the ruptures in the environment and ecosystem. Climate Funerary Art in its multitude of forms asks that we contemplate loss, what is being lost, what is being implicated in this loss and chaos, and how to care for what remains. If Max Ernst’s image of Europe after the war is a cautionary tale for the future generation, it behooves us to heed the lesson and reassess our priorities.

Top image: Max Ernst, Europe After the Rain II, 1940-1942

Examples of Climate Funerary Art

Sources

- Cunsolo, Ashlee. “Climate Change as the Work of Mourning.” Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief, edited by Ashlee Cunsolo and Karen Landman, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/ethicsenviro.17.2.137

- Demos, T.J. “Rights of Nature: The Art and Politics of Earth Jurisprudence.” Nottingham Contemporary, 2015, https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.ucsc.edu/dist/0/196/files/2015/10/Demos-Rights-of-Nature-2015.compressed.pdf

- Eng, David L. and David Kazanjian, eds. Loss: The Politics of Mourning. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003, https://books.google.com/books?id=JkNoeXNopDQC&pg=PR5&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Groys, Boris. “On Art Activism.” e-flux, June 2014, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/56/60343/on-art-activism/

- Lee, Jae Rhim. “My Mushroom Burial Suit.” July 2011, https://www.ted.com/talks/jae_rhim_lee_my_mushroom_burial_suit

- Solnit, Rebecca. “’The Impossible Has Already Happened’: What Coronavirus Can Teach Us About Hope.” The Guardian, April 7, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/07/what-coronavirus-can-teach-us-about-hope-rebecca-solnit?

- Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003