An Art Review by Carol Joo Lee

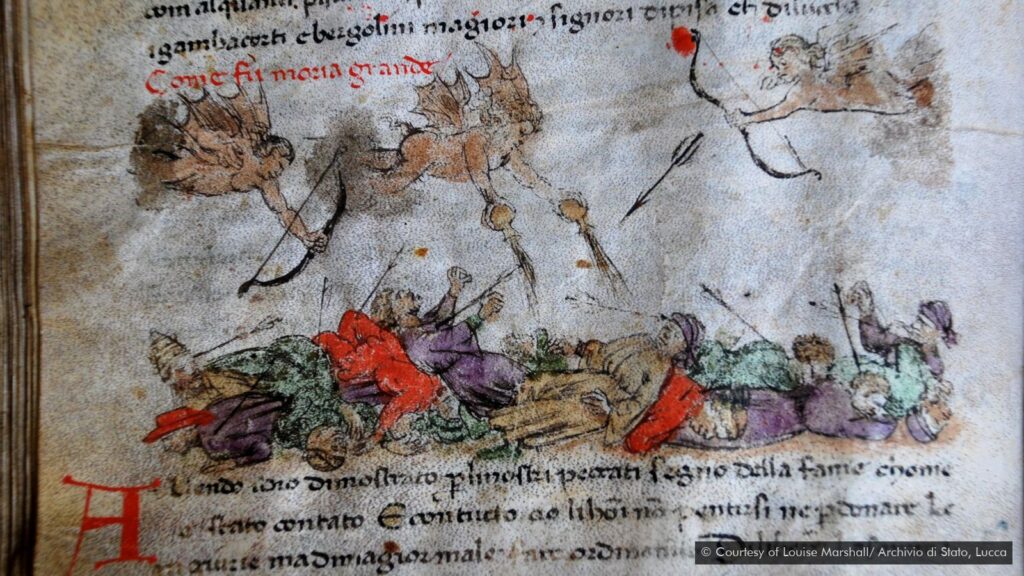

To talk about Climate Change is to lament what we have lost – land, water, air, and the species that depended on them, human and non-human. The onset of the sixth mass extinction looms large over our collective minds – at least those who don’t deny the indisputable data – and it creates existential conditioning that vacillates from dread to despair. Throughout history artists have been moved to memorialize the losses and traumas that have been inflicted upon humanity: a 14th century illustration depicts Black Death; Poussin’s “The Plague of Ashdod” records the horrors of the plague outbreak of the 17th century; and Picasso’s 1937 “Guernica” captures the inhumanities of Nazi bombing. In the face of tragedies of epic scale, art can universalize the unimaginable and humanize the incomprehensible. Contemporary artists of the Anthropocene, for many decades now, have tried to contextualize, eulogize and memorialize the losses/deaths stemming from ecological and environmental collapses. Essentially, the losses spurred by the Climate Crisis is the loss of home – literal and metaphorical, biological and geological, material and immaterial, multitude and one.

“I control the pain. That’s really what it is.” – Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Felix Gonzalez-Torres‘s works do not explicitly speak of the climate. Nonetheless, they exemplify governmental negligence and political inertia during the AIDS epidemic, which began in the 1980s, thus in the wake of the woeful bungling of the Covid-19 pandemic on the part of the federal government and the continuing denialism of Climate Crisis, it seems apt to re-examine his most famous piece “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)” from 1991 in our current context. Commonly referred to as “candy spill,” this participatory work, a mound of wrapped candies weighing approximately 175 pounds, the healthy weight of his lover before succumbing to AIDS, spill out from one corner of the room. As visitors take candy from the pile, the artwork shrinks then eventually disappears altogether. The candy has a twin function – representing the body and the placebo. In taking the candy, the audience becomes complicit in the erasure and masking. The site of the installation becomes an in-situ memorial to his lover and all who perished during the AIDS epidemic. It is sweet and heartbreaking. It is also a foretelling of Gonzalez-Torres’s own life, who died 5 years later of the same disease. We can very well imagine the mound of candies as our home, Earth, and the work, already powerful, begins to take on a whole new meaning.

How, when, and why do we invest culturally, emotionally, and economically in the fate of threatened species? What stories do we tell, and which ones do we not tell, about them?

– Ursula Heise

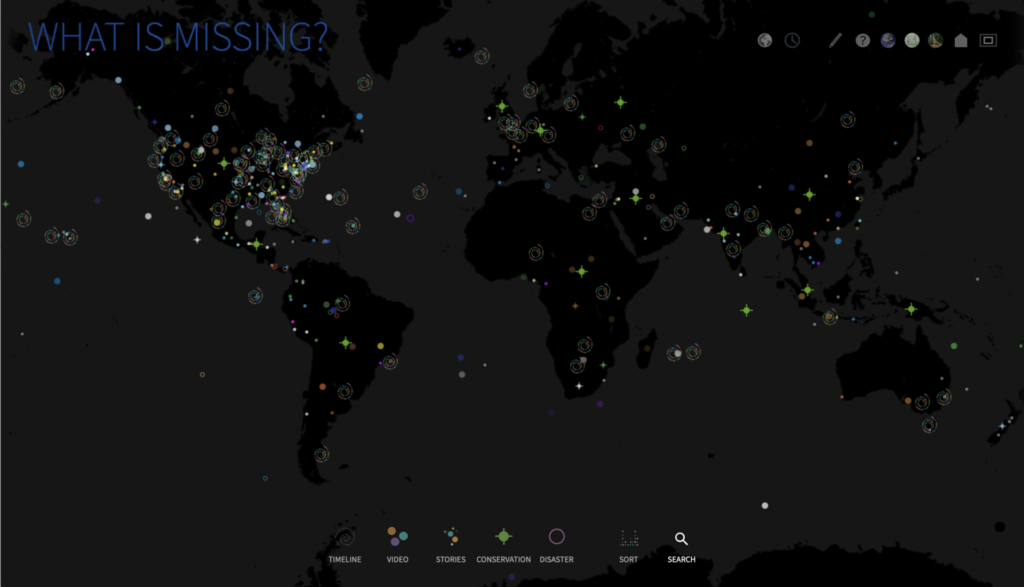

“What Is Missing?” is an interactive web project spearheaded by artist and architect Maya Lin, who’s most well-known work is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. No stranger to liminal sites where the dead and the living collapse to create a third space, Lin’s “What Is Missing?” is a portal of remembrance, reacquaintance and resurgence that works on several levels: a digital tribute to the now extinct species; an anthropogenic record of places; and a depository of people’s personal biocentric memories of “what is missing.” Flickering dots of various colors and shapes indicating different categories like disaster, conservation, timeline and stories across the darkened map of the world bring to mind constellations in the night sky. One can click on East Asian Cranes (coming back) or Heath Hens of Martha’s Vineyard (extinct) and get an overview of their survival history dating all the way back to 600 in the cranes’ case and 1620 for the hens. Launched in 2009 and updated up to 2018, the site itself feels like a digital relic given the further exacerbation of the planetary conditions under which all living species struggle to survive, and losses of an untold number of species from our biosphere since the site’s launch.

In 1982, Hungarian American land artist Agnes Denes transformed 2 acres of landfill in lower Manhattan into a wheat field. Created at the foot of the World Trade Center and a block from Wall Street, the golden patch of agriculture, titled, “Wheatfield – A Confrontation,” on the land valued at $4.5 billion, which has since become Battery Park City, was “an intrusion of the country into the metropolis, the world’s richest real estate.” Denes and volunteers cleared the piles of trash brought in during the construction of the Twin Towers, then dug furrows and sowed seeds by hand. In four months time, the land yielded 1000 pounds of wheat. The harvest became horse feed for the city’s mounted police and the rest traveled to twenty-eight cities around the world in an exhibition called “The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger.” The seeds were also given away in packets for people to plant them wherever they may end up in. Denes, in her prescient ways, was calling attention to what she deems as our “misplace priorities”: “Wheatfield was a symbol, a universal concept; it represented food, energy, commerce, world trade, and economics. It referred to mismanagement, waste, world hunger and ecological concerns.”

The harvest also marked the end of the physical artwork but the idea lives on through the visual documentation which offers a surreal angle and an uncanny audacity imbedded in the work. It is a rather strange coincidence that the work happened 19 years before the destruction of the World Trade Center and we are now 19 years out from the 9/11 attacks. In 1982, the field was a living, breathing counterpoint to the unbounded appetite for capitalism. Today, the work, at least the photographs with the towers in the background, function as a memorial for both.

Whether imbued with soft activism like Lin’s digital project or offering interventionist criticism like Dene’s wheat field, art under the umbrella of environment and climate challenges may not offer solutions but by showing and making us confront the losses and our lost ways, art does what it has always done throughout history, it reveals the nature of our time.

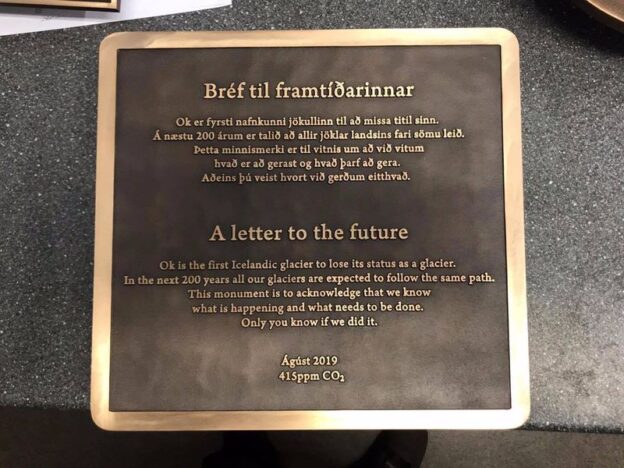

Top Image: Plaque Memorializes First Icelandic Glacier Lost to Climate Change

(Dominic Boyer/Cymene Howe)