Andres Malm’s “Long Waves of Fossil Development: Periodizing Energy and Capital” analyzes how the historic phases of capitalism’s evolution required technological leaps in the sources of energy that drive production. Based on Russian economist Nikolai Kondratieff’s theory that capitalism moves in waves consisting of “two phases: an ‘upswing’ characterized by boom conditions, succeeded by a ‘downswing’ of persistent stagnation” (162), we can see how the first long wave of capitalism beginning around 1780 denoted by water-powered industries such as cotton and iron gave way to a second wave propelled by steam, a third run on electricity, the fourth driven by gas and oil, and the fifth long wave we are currently in, typified by computerization of the economy. The transitioning from one long wave to another is not even, incremental growth but rather “proceeds through upsetting contradictions…which impel the expansion and renew the momentum again and again, and it might be these contradictions and the convulsions they generate that do most to produce and reproduce the fossil economy on ever greater scales.” (162).

But it seems that now we have come to an impasse because science is unanimously conveying that humankind has thrown off the balances and processes of the Earth System due directly to continued, elevated levels of C02 emissions from burning fossil fuels. And to reproduce the fossil economy on a larger scale than we are currently maintaining in the name of capitalist gain would have dire consequences to our planet and human civilization. Malm speculates that capitalism could instead propel itself into a sixth long wave by casting off fossil fuels and transition to renewable sources of energy which is exactly what humanity would require to prevent the disastrous scenarios of climate change. Solar, hydro, and wind powered technologies are already established and proven to effectively integrate into our electricity grids but still, our dependency on fossil fuels has not yet been curbed. Malm suggest that a “universal rollout” of these advantageous technologies might “breathe fresh air into languishing capitalism and ensure that we collectively back off from the cliff in time” (181).

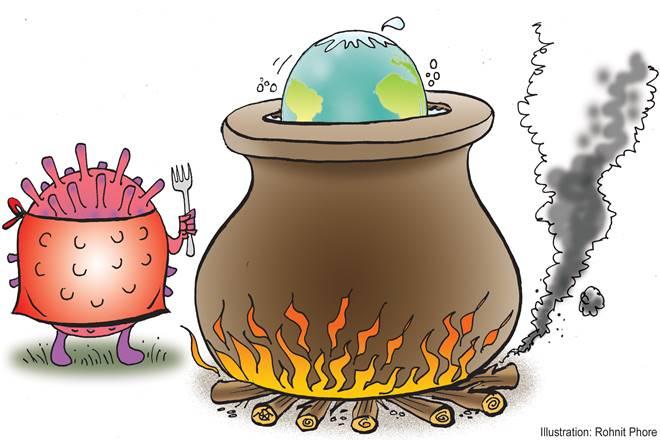

Following the theory of long waves of capitalist development and arguing that we have been on the downswing of the fifth wave since the global recession of 2008, Malm implies that we are in fact on the brink of a turning point to a sixth phase. Historically the transitions between phases “are determined by such unforeseeable events as wars and revolutions, the colonization of new countries, or the discovery of new resources—‘those external conditions through whose channel capitalist development flows’” (167). Our current state of affairs is, quite literally, a crossroads of “upsetting contradictions” inclusive of the consequences of climate change compounded by a global pandemic, severe economic downturn, and political and social instability. Could COVID-19 be the existential threat that pushes us past our paralyzed response to emissions reductions and the climate crisis into the sixth long wave?

Malm asserts that “the eruption of a structural crisis is usually attended by high unemployment, deflation or inflation, deteriorating working conditions, aggressive wage-cuts as capital seeks to dump the costs on labor and widen profit margins—all conducive to intensified class struggle” (171). And I would argue that we are amid these occurrences right now! But “capital has the power to “lay the foundations for a new epoch of expansion” by creating “a technological revolution, concentrated to one particular sphere” (171). Historical revolutions, between the first and the fifth long waves of capitalist development have remolded the entire economy, reimagining the technologies of transport and communications systems time and again. “If new life is to be breathed into sagging capitalism, it must come in the most basic, most universal guise: energy” (172).

Malm contends that renewable energy technologies “perfectly fit the profile of a wave-carrying paradigm” (181). They are of virtually unlimited supply, allow for costs to be reduced, and have vast potential for applications, “causing productivity to spike, spurring other novel technologies — electric vehicle charging systems, smart grids managed online, cities filled with intelligent green buildings — opening up unimagined channels for the accumulation of capital” (181). The groundbreaking innovation of switching completely to renewable sources of clean, emission-free energy would inevitably call for new government policies and financial systems, public education, and an overhaul of our behaviors and habits. Malm worries that “society, however, is slow in adapting, for unlike technology, social relations are characterized by inertia, resistance, vested interests pulling the brakes, always lagging behind the latest machines” (174). We have seen just that when new, renewable energy technologies emerge. They are initially received by society as a shock and spur push back in the form of skepticism, NIMBYism, etc. which must be overcome in order for them to take hold. In our current situation wherein the COVID-19 pandemic is threatening both global health and economic security, exacerbated by elevated social and political unrest and the ever-looming climate emergency, perhaps a paradigm shift in society at large is inevitably and necessarily what is being set in motion.