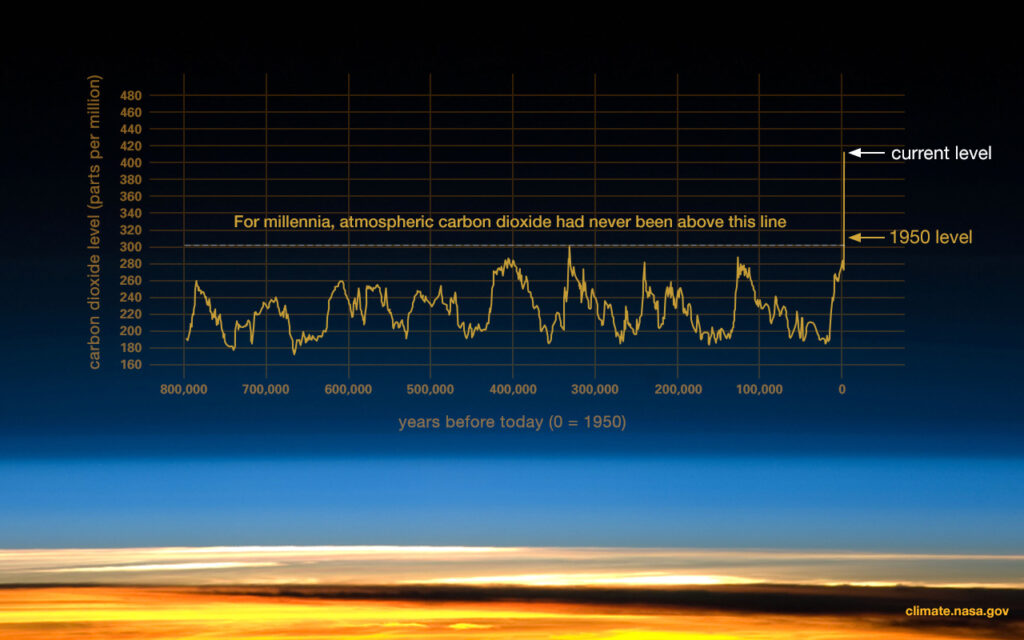

We need a better, more truthful and more accurate term for ‘climate change’. ‘Climate change’ is too vague, with too much space for doubt and not enough of the dynamism the term needs to convey. We’re at a turning point, with perhaps less than a decade to prevent further climate collapse and hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths of people and the continued mass extinction of animal and plant species. At this point, whatever we do will transform the planet. Communicating this is essential, both the problem we face and the solutions to it. Through writing and podcasting, language is the main tool I use for communicating my ideals, which are rooted in climate justice. Language is culture, too, and language influences how we think and vice versa.

I look at the research of Dilling and Moser for insight into where communication turns to action, and where it does not. Many thinkers have grappled with these issues, and I learn that the term ‘climate change’ has been deliberately used to obfuscate the danger implicit in it’s effects, and writers like George Monbiot, Rebecca Solnit and Eileen Crist want terms to reflect both the violence of some humans toward the planet and the beauty of this planet. Other scientists and scholars like Robin Kimmerer and Glenn Albrecht argue for new terms to be adopted instead of English words, either from Native languages or made up completely.

I believe many of the terms we use in climate discussions are lacking – I will investigate how language has deliberately been used to obfuscate this growing threat, and argue that a new, more emotive and more powerful lexicon is needed to convey the urgency of the nightmare we are facing. My focus is on the term ‘climate change’.

NASA and The IPCC use the term ‘climate change’ because it is scientifically accurate, but I argue that is not enough. The writer Rebecca Solnit does not mince words. “Climate change is global-scale violence, against places and species as well as against human beings. Once we call it by name, we can start having a real conversation about our priorities and values. Because the revolt against brutality begins with a revolt against the language that hides that brutality.” This is a clear call to action for those of us in the words business; if climate change is violence, then we need to call it that.

Climate crises caused by industrialized nations have ruined homes and livelihoods across the Global South, but industrialized countries do not refer to themselves as displacers, it stays a noun. If we in the Global North admitted to causing displacement, we would surely have to compensate in the form of climate reparations or open borders. That is…unlikely. The passivity of a language that relies on nouns helps to disguise our behaviour, and to take agency away from the creatures and things we describe. I learned from reading Robin Kimmerer that there are other languages, namely her ancestral language Potowatomi, that are largely made up of verbs. This is ‘the grammar of animacy’ and is useful for those of us who want to repair our relationship with the planet. So we see that the English language is not always up to the task, and needs to borrow from other languages or new words.

I settle on ‘climate crises’ as my preferred term, as it implies the serious nature of the mess we are in, but also the opportunity to turn it around. I discover in this paper that it’s more than words we need to change, it’s actually our relationship with the planet and all of the creatures and even ‘things’ around us that we need to transform if we are to thrive here. Words are a good start though, as is silence when needed.

Some resources

- Moser, Susanne C. and Dilling, Lisa. Communicating Climate Change: Closing the Science‐ Action Gap: The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Edited by John S. Dryzek, Richard B. Norgaard, and David Schlosberg. Oxford University Press, 2011

2. Crist, Eileen, “On the Poverty of Our Nomenclature”, Environmental Humanities, volume 3 (November 2013): 129-147. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/6904

3. Monbiot, George. Forget ‘the environment’, we need new words to convey life’s wonders. The Guardian Newspaper, August 9th 2017.

4. Albrecht, Glenn. The Importance of Language: “the expansion of my language means the expansion of my world”. From Glennalbrecht.com June 22 2020

5. Kimmerer, Robin. Speaking of Nature: Orion Magazine, June 2017

6. Klein, Naomi. “Call Climate Change What It Is: Violence” The Guardian, April 27th, 2014

7. What’s in a Name? Global Warming vs. Climate Change, NASA website August 16 2020