In the realm of market economics, though there are several schools of thought, one common denominator remains: the market should be optimized for sufficient gains and growth. As a former economics student, I recognize the importance of governments to balance the desire to sustain economic growth with that of other variables. From Brady Bonds to the market/controlled economy of China to carbon tax initiatives, different economic strategies have been deployed to deal with a host of problematic scenarios from developing countries embroiled in debt to a Communist country wanting to reap the benefits of market economics without succumbing completely to its free enterprise model to the ongoing and existential threat of Climate Change, which, taken to its most logical extreme, represents the most severe threat to our world (not that debt riddled countries and countries desiring to hold onto their customs aren’t important).

Such logic pervades Olivia Bina and Francesco La Camera’s research paper, “Promise and shortcomings of a green turn in recent policy response to the ‘double crisis,’’ which brings into question the efficacy of market economics as an economic system to address the ongoing environmental crisis and a framework to handle contemporary and future economic issues. Bina and La Camera consistently cite “Ecological economics,” drawing on the work of the subfield’s founder, Georgescu-Roegen, whose pioneering work demonstrated the limiting factor of a market economic world is natural capital, for “Historically, the limiting factor that focused attention was that of manmade capital, but as humanity’s impact on resources and the biosphere move us closer to the so-called Anthropocene (Schellnhuber et al., 2005) and to growing scarcity of natural resources (MEA, 2005; Rockström et al., 2009), the limiting factor shifts to natural capital” (2311).

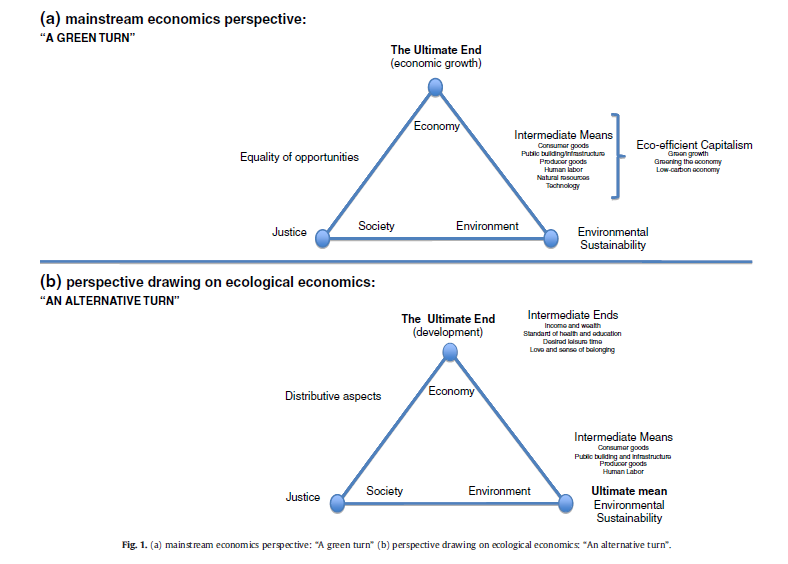

The idea that growth is unsustainable and cannot be endless is central to ecological economics and with that, Bina and La Camera offer an alternative model to modern economies privy to both environmental and economic crises (during a ravaging pandemic, a global recession and unrelenting environmental catastrophes, this article feels far too familiar). In their model (see above), aptly labeled “An Alternative Turn,” “Distributive aspects” replaces “equality of opportunities” in the “mainstream economics perspective” of a system of economics centered around bettering both environmental and economic crises, “Eco-efficient Capitalism.” On this model, the researchers explicate that “justice becomes the expected outcome of a redistribution of wealth through the initial equality of opportunities and, at global level, the ‘trickle down’ effect, whilst sustainability is secured as a result of eco-efficient capitalism” (2314). In contrast, Bina and La Camera’s proposed model “requires that the environment be considered an ultimate means (i.e. not substitutable)” for it “envisages the ‘Ultimate End’ linked to a development that embraces the moral and ethical dimensions of the relationship between humanity and the environment” (2314).

In essence, if there is not a significant recall of the market economics model, the current trajectory of the Climate Change crisis may result in a “Green” economy, but, as Bina and La Camera show, if the overarching goal of the model is to sustain economic growth, treating environmental sustainability as an added benefit of the model, the type of systemic overhaul needed to mitigate the damage of Climate Change won’t come from such a model.

In the article, Bina and La Camera keep referencing “Robert Skidelsky’s (2009) observation that economics is the ‘tutor of governments,’” underlining the importance of alternative economic models mainly focused on fighting the Climate Change crisis. Skidelsky’s classification of the role of economics in government is on point and though this paper was published in 2011, a wealth of literature has since been published on economic modeling centered on Climate Change. If economics is indeed the tutor of governments, then we should continue to act as facilitators of education for the pupils that are our governments, bridging gaps between disparate fields and disciplines as we work to better the gap between our present and future.