A Topical Analysis & Sort of Reading Response by Carol Joo Lee

One of the most indelible images of this unprecedented time of Covid-19 is of a dismayed farmer in a field littered with his rotting crop. Another is a line of cars stretched on the highway beyond the frame of the picture outside a food bank – the location could be Anywhere, USA – awaiting hours for a box of groceries. As we witnessed these two heartbreaking, non-intersecting worlds, we saw clearly, among the many systemic vulnerabilities the 2020 pandemic has exposed, the limits and dangers of our current ways of distributing food. As crop and dairy farmers across the country faced the grim reality of having to dump their produce, milk and eggs as schools, hotels and restaurants shut down, millions of Americans, laid off due to no fault of their own, were on the precipice of going hungry. Neither food waste nor hunger is a new phenomenon. However, it is something else to see them side by side, interlinked and unresolved. Many wondered upon seeing these two realities juxtaposed against each other, why can’t this food reach the hungry in an advanced country like ours? It was hard to argue with Rebecca Solnit, that “We are a country whose distribution system is itself a kind of violence.”

The pandemic put the strains of centralized food distribution systems under a microscope – we saw the failures plainly. It pulled the rug out from under our feet and as Bruno Latour asserts, the challenge became “much more vital, more existential… also much more comprehensible, because it is much more direct.” We were forced to “be concerned with the floor.” But Climate Change has been wreaking havoc on the status quo modes of food distribution for decades yet the government has done little to improve the situation. According to EarthIsland.org, In New York City, most of the 5.7 million tons of food that arrives in the city annually passes through Hunts Point Distribution Center, the largest wholesale market in the United States, which sits on the edge of the Bronx River, surrounded on three sides by water. Almost all this food comes by truck – nearly 13,000 semis each day.

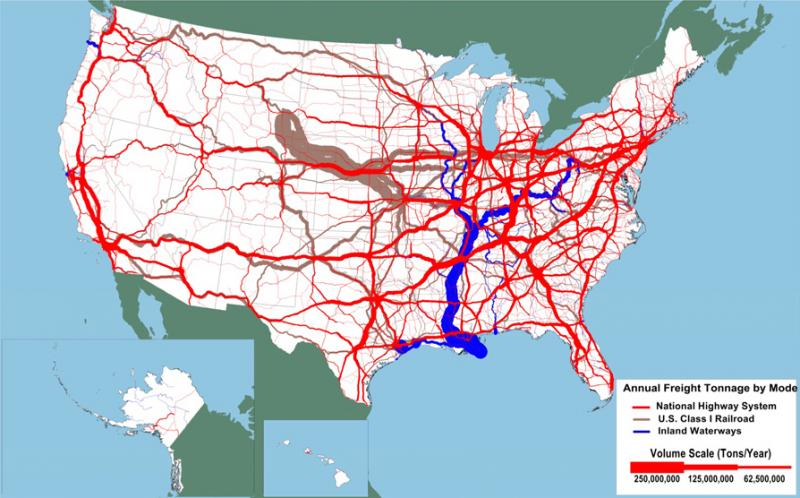

The structure was spared during Hurricane Sandy but traffic restrictions and road damages in other parts of the city caused a major disruption. The hurricane also triggered power outage causing refrigeration and payment systems failures. This is just one example of how a perfect storm of long-distance transportation, centralized wholesale markets, the concentrated food production under a natural disaster can paralyze food distribution affecting a large scale food waste and insecurity, especially to the already vulnerable population. In another instance, the severe drought of 2012 led to near-record low water levels of Mississippi River, a major transcontinental shipping route for Midwestern agriculture, forcing barges to carry lighter load and increasing shipping costs, which resulted in significant food and economic losses.

Distributional failure amplifies the obscene problem of food waste. Yale Climate Connections reports, 30% of the food produced globally is wasted every year. In the US, that number jumps to a whopping 40%. If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases behind China and the U.S., according to the World Resources Institute. These numbers are not entirely surprising, yet, nonetheless shocking and disturbing. The main factor in this scandalous amount of waste is over-production which also contributes to unnecessary GHG emissions. Add to these already grievous facts, unforeseen distribution breakdowns as we witnessed on the onset of Covid-19 lockdowns compound the food waste problem, which compounds the food insecurity problem. When I look at the faces of the people lined up for food in much circulated photographs during this pandemic, I suspect that I will see almost the same makeup of people in the near-certain future climate-related catastrophes that disrupt access and means to food – largely BIPOC, elderly and low-income.

The 2018 IPCC Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C filed “the impacts of global and regional climate change at 1.5°C on food distribution” under Knowledge Gaps and Key Uncertainties. It now seems, in the wake of a pandemic, the outlines that weren’t so clear two years ago have been brought into sharper relief. Though we may be lacking definitive data, on a visceral level, the impacts are and will be widespread, panic-inducing and life-threatening. As we strive for mitigation and adaptation to 15°C pathways, alternate and equitable modalities of food distribution systems are critical in reducing poverty and inequalities, as well as GHG emissions. In a larger sense, in Solnit’s words, Climate Change is not suddenly bringing about an era of equitable distribution. But surely, without concerted efforts to change the broken ways and redirect our climate and moral trajectories, there will be no rug and no floor to land on.