Core Text

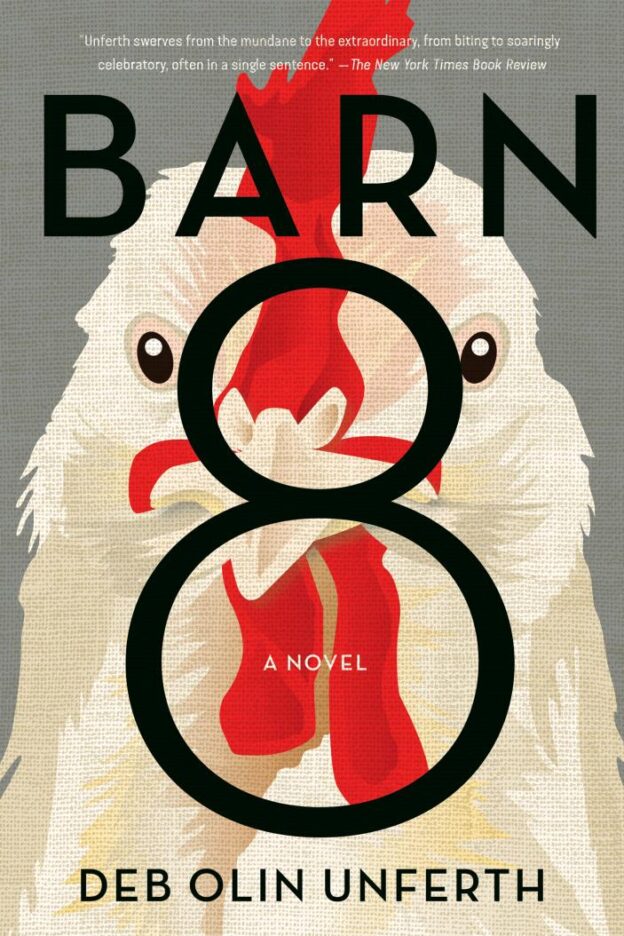

Olin Unferth, Deb. Barn 8. Graywolf Press, 2020.

Summary

This novel follows two egg farm auditors whose job is, well, auditing egg farms, in Southern Iowa “a gray land of truck stops, crowded prisons and monocrop farming.” Janey is one, a heartbroken young girl who from the outside has almost completely shut down, though we are the lucky readers who hear her inner life narrated, and know that she still has imagination and wit. Janey meets Cleveland, a seemingly strait-laced auditor “Expressionless face. A rigid way of turning her head.” But beneath Cleveland’s uniform beats the heart of a rebel, one who has recently started to rescue the hens she’s supposed to merely check on. When Janey joins her, the book really takes off. The women are bound together in an unusual mother/daughter triangle that sheds new light on that ever fascinating relationship, adding complexity and beauty. Auditing is a simultaneously banal and evil role, they see to it that regulations are being followed so that there is no hiccup in the flow of eggs to the American consumer.

The impetus to right a wrong, to do whatever tiny thing we can against something as inhumane and damaging as big agriculture, or rampant inequality, or racism? The characters in the book understand that it’s easy to feel helpless. But Janey and Cleveland’s voices telling their version of the planning and rescue, hearing their fears, jokes and growth, this is a pure delight. Janey can’t get used to the barns, packed with hundreds of thousands of crammed hens. “The unimaginable scale, the tiny beside the huge, the existential power of size.” But they do something, at least they try to. They plan a huge heist, to free the chickens. Others join in too, there’s Dill, the burnt out director of undercover investigations, and Annabelle, a radicalized farmers daughter, and there’s even Bwaaukk, the first rescued hen, a brave and dopey little creature. Deb Olin Unferth verbalizes the vague unease I feel living in this militarized and profit obsessed country that still manages to be full of wonderful people. “Think high-rises, gated communities, all the places that give you a twitch of existential dread. The Amazon shipping facilities, the dying superstores, the prisons and detention centers, the pig farms, all the boxes that hold products and people and animals, the LeCorbusian landscape one skirts over or through, avoids.” This book does not avoid those places, instead bringing us inside for a close-up look at big agriculture and self-styled eco-terrorism.

Resources

Olin Unferth, Deb. Cage Wars, A visit to the Egg Farm, Harper’s Magazine, November Issue, 2014.

This is a deeply-reported piece of long-form journalism from the author of Barn 8. In it, Olin Unferth traces the history of American egg production from the 1879 invention of the incubator through to the time of writing in 2014, taking in all of the regulations imposed on what became a massive industry. The writer describes the sight and sound of 147,000 chickens in cages in massive barns she visits, and includes expert testimony and insight from farmers and scientists. She makes contact with activists for this piece too, and while they do not reveal their identity, they send her DVDs of animal abuse collected by whistle-blowers. She sees battery farming herself too, and her depiction of the suffering and death therein is quite devastating. The piece ends on a sweet note of relief, with a group of former barn hens long ago given to an animal rescue center. They wander around outside with opened wings, sunning themselves and pecking about for worms.

Big Bird, Season 1, Episode 4 of Rotten, aired on Netflix US from January 5th 2018

Each hour-long episode in this documentary series follows the industry behind and production of a different food-source. This episode is about chicken farming, a massive and growing business in the US and around the world, with particular competition coming from China and Brazil. As a viewer, you will see inside the huge barns full of broilers, chickens bred specifically for meat. Corporations have a chokehold on the chicken industry and family farms get squeezed out, so this is about more than animal welfare or food production, it’s about neo-liberalism and a living wage for the people who work within. This documentary also depicts a terrible crime, when a disgruntled former chicken ‘grower’ killed thousands of chickens in neighboring farms after he was fired, with those farmers still seeking justice and compensation. We learn in the book about the cut-throat nature of poultry farming, and this documentary backs that up. This is an important look at what remains an opaque industry that in 2019 alone produced 9.2 billion broilers, in a country that eats more chicken than any other, with Americans consuming 98lbs of chicken per capita in 2019.

Lamarca, DSF, Pereira, DF, Magalhães, MM, & Salgado, DD. (2018). Climate Change in Layer Poultry Farming: Impact of Heat Waves in Region of Bastos, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science, 20(4), 657-664

This paper models the effects that climate change, as forecasted by the IPCC, will likely have on poultry farming in Bastos, a municipality in state of São Paulo, Brazil, specifically on layer farming. Layer farming is specifically for egg production, and this region accounted for 7% of they country’s egg production in 2015. It was also the scene of a mass chicken death, when over 500,000 chickens died during a 2012 heatwave there. The authors model using data from the IPCC and discover that worse and longer heatwaves are on the way, therefore they predict higher hen mortality in the future, unless the farms can convert to air conditioning. It’s vital to plan for the welfare of humans and animals in this industry as the environment becomes more deadly for both.

Discussion Questions

- Cleveland’s character has an arc, what is it and what are the pivotal moments throughout the book that we see it bend?

- The final chapter of the book mirrors the final scene in Olin Unferth’s non-fiction piece, where a group of former barn hens are living in relative freedom. How successful is this as a plot point? What emotions does it stir, if any? Does the contrast between the graphically depicted misery of a barn chicken with the glowing image of a free chicken motivate you to change your view point or actions when it comes to buying and consuming chicken or eggs?

- How would you characterize humanity’s relationship with both chickens and climate change in relation to these readings? Does this relatively inexpensive source of protein discount the fact that big agriculture (the chickens and the grains that feed them) are damaging our climate? And what about than the modeling done in Brazil predicting more mass deaths during climate events like heatwaves, will that change our relationship?